I have mentioned One Piece a couple of times before, so it should come as no surprise that I really love this series. There are many reasons why I love One Piece, but today I will be focusing on the overarching philosophy behind the series, which resonates deeply with me. Here, I’m going to argue that One Piece is a Romantic story, in the literary sense of the word.

First, what is One Piece? One Piece is a manga series created by Eiichiro Oda and published weekly on Shonen Jump since 1997 (impressive, right?). The series follows Monkey D. Luffy, a boy with a rubber body whose dream is to become King of the Pirates. In order to achieve his dream, he has to find the One Piece, a legendary treasure left behind by the previous King of the Pirates, Gold Roger1. Along his journey, he gathers a strong and loyal crew of fellow dreamers, and together they go on adventures of epic proportions. It’s a fun, action-heavy fantasy series that leans heavily into the bizarre.

Before we continue, we should also define what Romanticism is. The Romantic period in literature took place in the 18th century and was characterized as a response to the Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution. Romantic artists rejected the idea that the world could be explained through rationality, they valued the “sublime” and intense emotions, and they had an individualist outlook. Freedom to express their sensibilities was very important to these artists.

I’m going to make the case that Eiichiro Oda has incorporated many Romantic ideals into his magnum opus. This is not unintentional, remember that the very first chapter of the series is called “Romance Dawn”, and the characters even use the word Romance in the text to refer to the search for adventure and wonder. Oda is being deliberate here, and I believe that One Piece represents a modern kind of Romanticism. Without further ado, let’s begin.

Spoilers for the entire series!

Skypiea and the Age of Dreams.

After saving the kingdom of Arabasta from Baroque Works, the Straw Hat pirates set sail to the next island, now with a new member: the mysterious Nico Robin. She reveals that her true area of expertise is archeology, and she soon proves to be useful when a giant ship falls from the sky, and she deduces that the ship has been floating on the clouds for several centuries. This seems outlandish, but then their Log Pose starts pointing upwards, signaling that there’s indeed an island in the sky.

Thus begins the Skypiea Saga, one of my favorite parts of the series (unpopular opinion, I know).

The crew decides to take a quick stop on a nearby island, Jaya, to gather information. They make port on Mock Town, where the Straw Hats get in a fight with Bellamy, the captain of another pirate crew. Bellamy makes fun of the Straw Hats for believing in silly notions like islands in the sky and the One Piece treasure; he claims that the age in which pirates were motivated by dreams is over, and there’s a new age coming, one where pirates sail for the sake of money and fame, with no grand ideals or lofty aspirations.

The entire saga is defined by the conflict between opposites — realism vs. romanticism, the Skypieans vs. the Shandians, progress vs. tradition. We will focus on the first of these ideological conflicts.

Luffy is driven by a firm set of beliefs and a personal moral compass that doesn’t necessarily align with society at large, and there’s more depth behind his behavior than what it may seem at first glance. In Skypiea, we see Luffy stand by his core belief that dreams are worth dying for, and that a true pirate knows that the world contains more than riches and superficial glory. Being able to wonder at the beauty of the world is of the utmost importance. To Luffy, it doesn’t matter if the One Piece is real or not, the journey and the dream itself are real, and it’s the dream that drives him. That’s why he gathers people around him that are likewise motivated by things beyond material gain, people who are willing to appreciate the sublime and mysterious things in life. Logic and rationality can get you far, but what is it worth if you aren’t having fun?

To be a pirate, Luffy proclaims, you must be a Romantic.

Ultimately, Luffy triumphs over the cynic and “realistic” Bellamy, but he doesn’t need to gloat. He finds the Sky Island, the goes to the City of Gold, and he rings the bell to let the true believers down below that these things exist, and they can be reached, if only you are willing to put your life in the line to go there. The Age of Dreams is still alive.

Pirates are not heroes.

One important element of Romanticism is individualism, and we see this manifest in the way that selfishness is portrayed in One Piece.

Luffy is a deeply selfish person, though this doesn’t mean he’s uncaring. Above everything else, he wants to be free and have fun with his friends. While he often helps out people in need, this is not out of the good of his heart, but always motivated by some personal connection with the other person. He helps Vivi save her kingdom because he cares about her, he saves Skypiea because of Conis and her father, he liberates Wano because he made a promise to his friends, etc. Luffy helps others because of his selfishness, not in spite of it.

Let’s talk about Yasopp, Usopp’s dead-beat dad. While the audience is free to judge Yasopp for his actions, he’s never framed negatively by the story. This aligns with the individualism that the series promotes—Yasopp left his family to follow his dreams, therefore what he did is not a bad thing (according to One Piece’s moral system). Similarly, many of the characters have arcs about learning to be selfish and to pursue their dreams without caring about anything else, putting their desires first. Perhaps the best example of this is Robin, with her iconic “I want to live” scene being all about her realizing that it is okay for her to have dreams and desires, even if it means going against the world.

The Drums of Liberation.

Gear 5 is Luffy’s final form, his peak, and it’s described as the world’s most ridiculous power. It’s not just Luffy at his strongest, it’s Luffy at his most free (and Luffy’s dream is to become the King of the Pirates—the most free man in the world). With Gear 5, Luffy is able to not just make himself rubbery, he can now make anything rubber, or to put it simply, he can change the rules of the world and become a Looney Toons character. He becomes freedom itself.

Some people were not happy when Gear 5 debuted, thinking it was too silly. They were probably expecting Luffy’s final transformation to be some badass-looking, big-muscled guy. This comes from a fundamental misunderstanding of where Luffy draws his power from—his strength comes from his relentless whimsy and joy, not from how big his fists are.

Me? I was telling everyone I know about how epic Gear 5 was and smilling like a kid that just a got a new toy. I was having the time of my life.

Gear 5 is the final form of One Piece’s Romanticism, the manifestation of the philosophy that wonder, laughter and intense emotions are the most powerful things in the world. Freedom, One Piece proclaims, is being able to laugh in the face of cruelty, the ability to have fun in a bleak world.

Luffy’s heart beats to the rhythm of the Drums of Liberation. He’s an herald of freedom, bringing down oppresive regimes and tyrants. He believes that everyone should be free to laugh.

Bringing Romanticism to a modern, younger audience.

I think one of the strengths of the series is that it appeals to people from many different demographics, but it’s important to remember that the target audience is young boys. And I think these young boys are the ones getting the most out of these themes, unlike the grown adults arguing about power scaling or even people like me that obsess over the literary value of the series. At the end of the day, none of this matter as much as the fact that the series teaches children that they should dream.

We live in an increasingly bleak world, where cynicism is taking hold and people are afraid of being genuine. We fail to appreciate the beauty and grandeur of life. One Piece proclaims that we should still look for adventure, we should have larger aspirations than making money, that freedom and wonder should be real values to live by. Eiichiro Oda is asking his readers to become Romantics, and he’s doing it in a way that catches the imagination of young kids, through whimsy and silliness, without fear of being seen as cringe, weird or too earnest.

In case it wasn’t clear, I love One Piece. I’m extremely happy to be able to see this wonderful story come to an end, and I can’t wait to see how Oda is going to wrap everything up. One Piece has brought whimsy back into my life, and there are few stories that make me feel this much joy and love for the world. To me, the relentless Romanticism of One Piece represents a bright spot in our irony-poisoned, carefully-detached, pessimistic society.

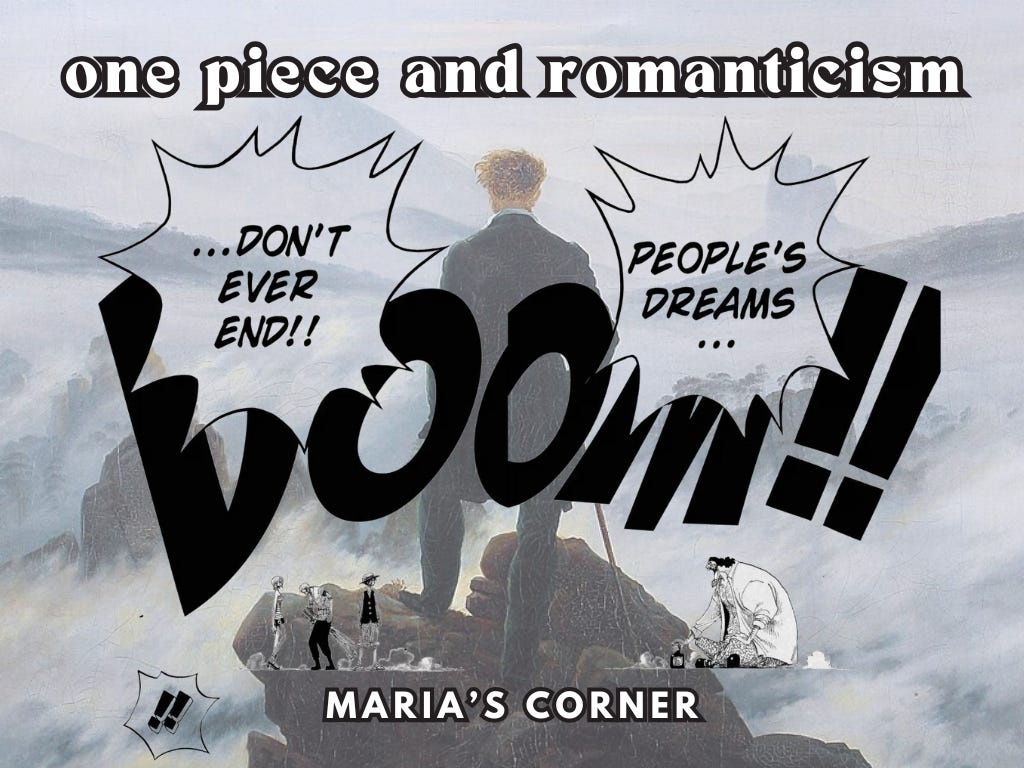

In other words, this is what Luffy was thinking when Bellamy started talking shit:

Dreams never die, the world is full of beauty and wonder, and anyone trying to convince you that being earnest is cringe is a loser.

Further Reading:

The Romanticism of One Piece by tumblr user creative-type. This meta analysis was my main inspiration for this essay, and it also goes over how the Romanticism in One Piece is different from the Romanticism of the 18th century. I highly recommend reading her other analysis posts. She’s also the creator of One Piece Backgrounds, a blog dedicated to rereading and picking apart the manga to find interesting things that often go overlooked. She’s currently covering the Sabaody Archipelago arc.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoy what I do but are not ready to become a paid subscriber, you can support me on Ko-Fi, where you can decide how much you want to pay. If you want to read my paid posts, consider subscribing for just $5 a month. Paid subscribers will receive at least 1 extra post each month, and my full reviews for finished series will be paid-only.

I know his real name, please don’t come at me for using the non-spoilery version. The post already has enough spoilers as it is.

I think the idea of romanticism and the series overall being targeted to younger audiences works really well and is good to point out. As adults we lost for the most part to see the world through such innocent lens and Luffy himself is probably the most innocent in the series, only following his whims to let him be free. Great read!

Have not read One Piece but really enjoyed this analysis. It always does me good to see popular/'kids' media discussed in terms of literary movements.

I kind of wonder if there was any cross-pollination between One Piece and Berserk, which is a very different beast (and began about a decade earlier), but there is some overlap - Berserk also had a lot to say about dreams and dreamers, and the magnetism of a leader who pursued his dream single-mindedly and selfishly (Griffith), and inspired others to do the same. Griffith is also often likened to Napoleon, a major 'hero' and dreamer of the Romantic era.

Will definitely write more about this at some point - my feeling is that Berserk is actually much more Existentialist, and therefore very post-Romantic in nature, hence Griffith becoming the villain (as Existentialist Dostoyevsky thought of Napoleon and other 'great men' of history), while the hero Guts constantly ponders the meaning (or lack of meaning) of life.

However, Berserk also ends up featuring pirates, young boys with shonen-esque ambitions (Isidro), and a lot of whimsy and wonder (elves and witches). So perhaps there is some relationship with the Romanticism of One Piece and shonen generally.